We know from Pliny the Elder that in Rome on the Field of Mars (Campus Martius), the erection of an Obelisk (shipped from Heliopolis, Egypt in 10BC) was finished in BC9.

In January BC9, near the obelisk, the shrine Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Peace of Augustus) was completed, too.

Another name for the above Obelisk, including its supposed sundial function, is Horologium Augusti or Solarium Augusti (the Solarium of Augustus). The obelisk is a “gnomon” (vertical shadow-caster) whose possible various functions are partly disputed today. According to Pliny, it was not only the obelisk itself that served as a shadow caster on the pavement of the Field of Mars. The shadow of a gilded bronze sphere, the “gilt ball” (aurata pila) mounted by a rod on the “pyramidion” (small pyramid) at the top of the obelisk played an important role, too.

Emperor Augustus dedicated his obelisk to the God Sun, Latin “SOL”.

You can watch the almost 5-minute video of Professor Bernard Frischer and his fellow researchers about the simulated antique Mars field.

The obelisk collapsed in the 9th or 10th century, was buried, and was found in 1512. In 1789, it was re-erected in Piazza Montecitorio (south of its original location), where it is still on display today (that is why now known mainly as the Montecitorio Obelisk.) The restored Ara Pacis is also not on display in its original location but in a new museum in Rome, built especially for the reconstructed version.

The two monuments were not only built at the same time but are also linked in other ways. One of these links is the topographic alignment of the two objects, namely, the sides of them are axially turned to each other. When I refer to both “objects” simultaneously, I will call the pair of Horologium Augusti and Ara Pacis together briefly as the “HAAP” in this blog.

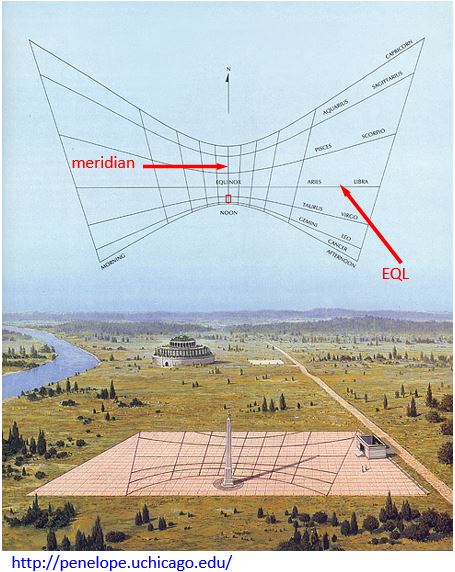

The way any gnomon works is that the peak of its shadow virtually draws lines on the horizontal surface, as shown in the figure below.

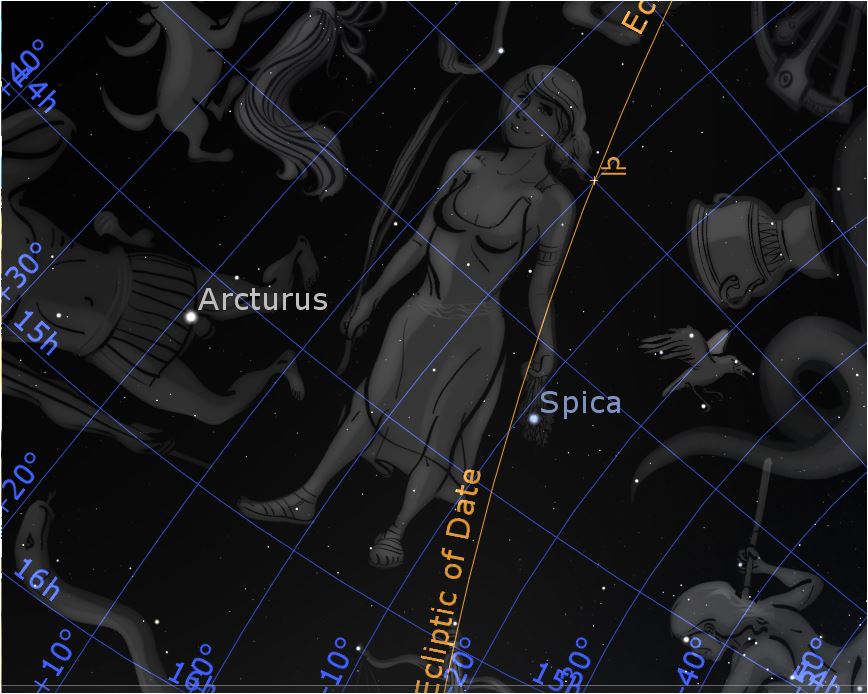

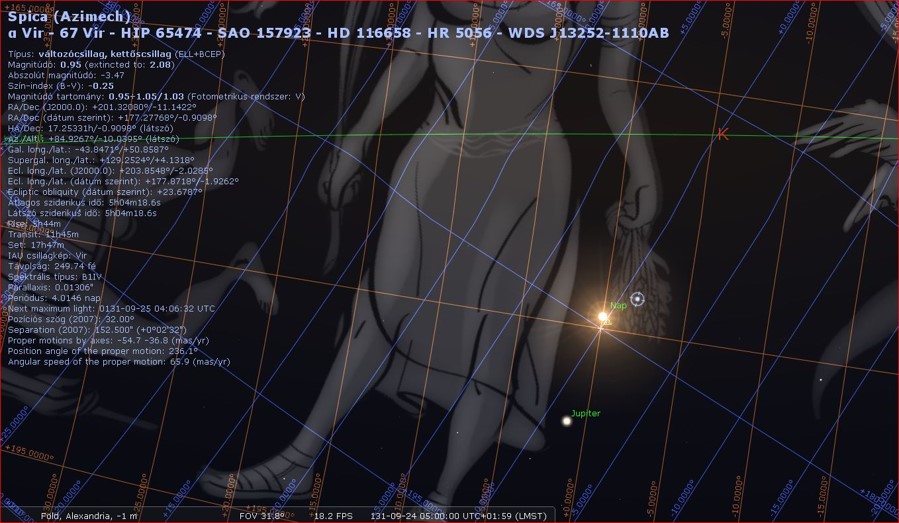

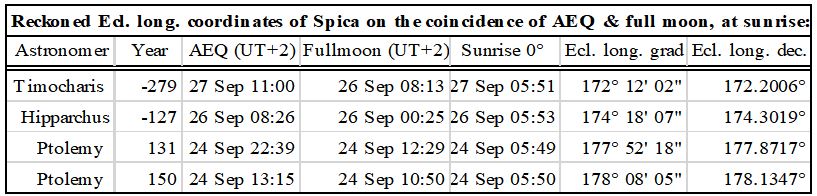

Exactly at local noon, the middle of the shadow line of the obelisk itself shows from South to Nord along the meridian, the line running S-N across the vertical axis of the obelisk in the horizontal base plane. The direction of the obelisk’s shadow shows the local noontime on each day of the year as usual by gnomonical instruments. Using the sphere’s shadow, the meridian markings can indicate the sun’s position every noon of the year. On the day of the equinoxes (VEQ and AEQ), the shadow of the gilded sphere follows the so-called equinoctial line (EQL, perpendicular to the meridian line) along the West-East direction from sunrise to sunset.

Based on the above facts, the functions usually assigned to Horologium Augusti and Ara Pacis (HAAP) are the following:

- Meridian function

- Equinoctial function

- Sundial function

- AEQ-birthday function

Meridian function:

According to the experts, the length of the shadow at noon, i.e., the position of the shadow of the gilded sphere indicated the day of the year, or more precisely, mainly seasonal time boundaries during the year, like the weather- and wind- changings. The shortest shadow belongs to the longest daylight of the year at Summer Solstice (SUS), and the longest shadow belongs to the shortest daylight of the year at Winter Solstice (WIS). In 1980, the renowned German archaeologist Edmund Buchner found bronze gravings in the antique pavement marking the meridian. Due to this archaeological find of Buchner, the obelisk’s “meridian function”, which is virtually a “noon sundial function”, became certain.

Due to the height of the obelisk, the length position of the spherical shadow on the meridian changed on the calendrical VEQ and AEQ day of the successive years. This change happened in a cycle of four years. The measure of the change was sufficient so this made the Horologium Augusti a suitable instrument to show and prove the correctness of the four-year leap year cycle of Caesar’s new calendar. However, the change in shadow length remained in a narrow band at noon on VEQ day and AEQ day of the different years.

Equinoctial function:

Because of the existence of the theoretical equinoctial line EQL (which is virtually a narrow equinoctial band if we examine many years), some researchers state that the days of the equinoxes (VEQ and AEQ days) were also indicated by the west-to-east tracing of the shadow of the obelisk’s gilded sphere, from sunrise to sunset, along the EQL. There is no historical record or archaeological evidence of this equinoctial function. No equinoctial signs like the meridian signs in the antique pavement have been found on the Field of Mars.

Sundial function:

Pliny did not write about a sundial. However, following the opinion of Edmund Buchner, the obelisk is generally considered a colossal sundial (Horologium, solarium) with a horizontal clock face. Buchner based this partly on earlier opinions and partly on his own considerations. Buchner’s hypothesis is logical because gnomons were often used as a sundial. However, no ancient descriptions or archaeological evidence of a complete sundial function (according to the above image) has yet been found on the Field of Mars.

AEQ-birthday function:

According to Buchner, the obelisk and the Ara Pacis were not only built but also designed together and functionally linked to form a “cooperating architectural ensemble”.

Buchner considered one of the main tasks of the obelisk to be to cast the shadow of the golden sphere on the altar of Ara Pacis on the day of the AEQ, which was the same as the birthday of Emperor Augustus, 23 September. According to Buchner, this could symbolise that the emperor’s mission from birth (natus ad pacem) was to establish peace. But Buchner did not know in 1976-1980 exactly on which day AEQ fell in BC9!

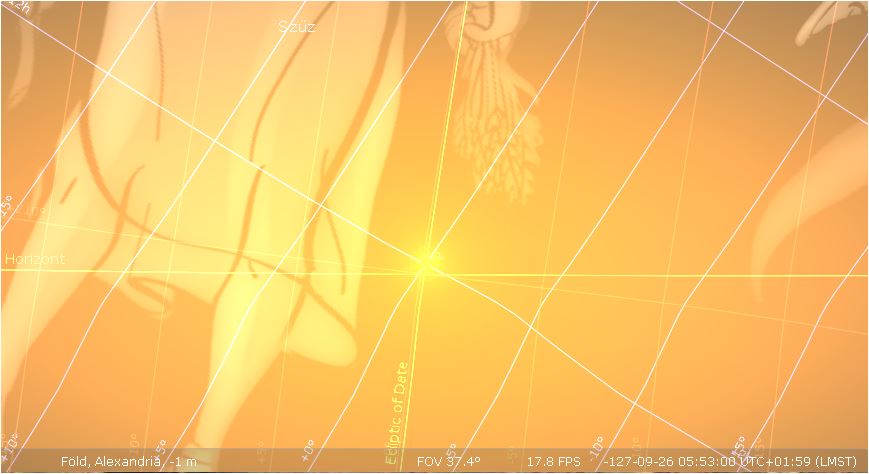

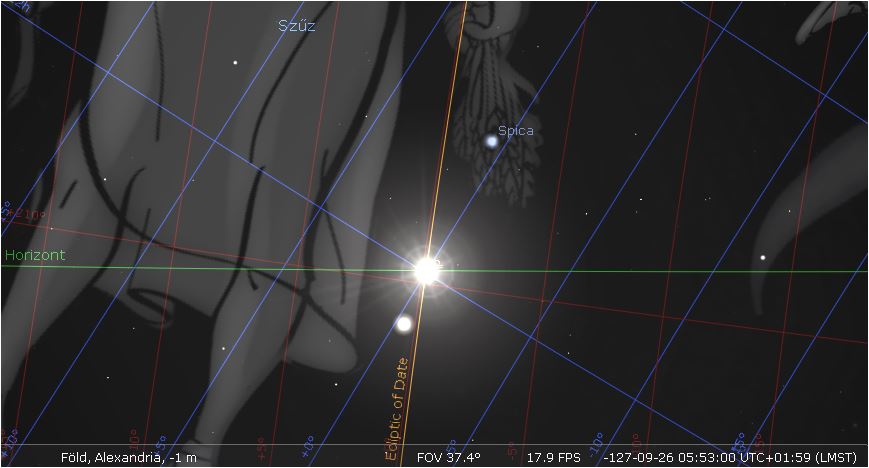

Namely, in BC9, the AEQ fell on 25 September and therefore did not coincide with the birthday of Emperor Augustus, as we have already seen!

According to a recent Astro-archaeological digital simulation (Prof. Bernard Frischer et al.), on 23 September 9BC, the sun was still so high that the obelisk’s shadow was too short, so it could not reach the western opening of Ara Pacis, let alone the altar. A few minutes later, when the shadow was longer and could have got the “door”, the shadow had veered more off the opening and turned south, moving to the south outside wall of the entrance.

So, Buchner’s AEQ-birthday function did not work in BC9!

However, on 25 September BC9, the day of the AEQ, the shadow of the golden sphere could already reach the threshold of the Ara Pacis too. But even on this AEQ-day, the shadow did not reach even the western sidewall of the altar table.

It is a fact that the EQL topologically points towards the altar of Ara Pacis. Indeed, on the day of AEQ, the shadow of the golden sphere moved along the EQL towards the western entrance and altar of Ara Pacis.

For me, based on astronomical considerations, this means the following:

The spatial position of the AEQ, as seen from the earth, is stable, resulting in relatively stable Sun lights directions on the AEQ days of every year. The required shadow angle of incidence occurs on the AEQ day of each year. Even the corresponding shadow length produced on the AEQ day of each year shows only a slight length difference.

On the AEQ day of different years, the time of occurrence of a given shadow direction changes year by year only with some minutes. The variation in the shadow length associated with the AEQ day falls within a narrow interval in different years. If the Horologium were still stable standing today, the shadow length of Obelisk would fall within this narrow band even on the present AEQ day. I have verified these facts by Stellarium calculations, which are not detailed here.

In my view, the Obelisk-Ara Pacis complex was designed and built to be strongly linked to the AEQ day. (In an astronomical and not calendrical sense). We will see in the next blog how "special" the Horologium many years long functioned on the astronomical day of AEQ. The day of AEQ fell not in 9BC but, as we have already shown, 220 years later, in 212CE, on the calendrical and at the same time on the astronomical birthday of Emperor Augustus.