Since the lunar month is approximately 29.5 days long, the oldest version of the early Roman lunar calendar, which dates to before the state’s founding, probably had months of 29-30 days, alternating.

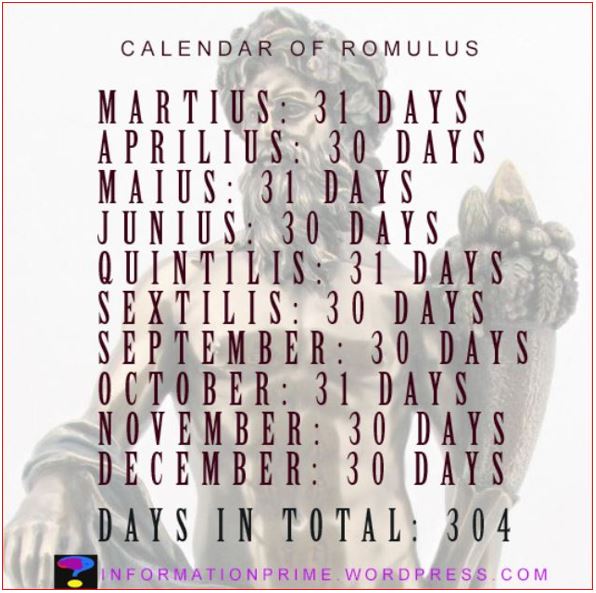

Over the centuries before Caesar’s reign, the old Roman lunar calendar underwent several profound transformations. Already Romulus or Numa Pompilius had increased the length of the months. The year began with March, and only ten months were given names or numbers. This lunar calendar of 304 days was created, with four named months (Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Iunius) and six numbered ones (5th-Quintilis; 6th-Sextilis; 7th-September; 8th-October; 9th-November and 10th-December). However, these ten months did not make up a solar year, so a two-month anonymous period was inserted into the period of winter inactivity.

Later, the onset of winter got the names Ianuarius and Februarius; the calendar had 12 months. The calendar year would have been only 354 days long in standard years, but it was extended to 355 days because of superstition. For this purpose, the length of the months was changed. Four months of 31 days, seven months of 29 days and February of 28 days resulted in a 355-day year. The structure of the Republican 355-day calendar is presented in the next chapter.

Meanwhile, in 153 BC, the first day of the year was moved to 1 January, when the new officials took office.

This would not have been sufficient for the revamped calendar to build a solar year. Therefore, 22 or 23 “leap days” (intercalation) were alternately inserted between 23 and 24 February every two years. Formally changed the length of February (including the intercalary months if needed) according to the sequence: 28 days or 50 days, and 28 days or 51 days.

The duration of the four-year cycle was thus 355+377+355+378 = 1465 days.

However, this made the years about one day too long; on average, 1465/4 = 366.25 days.

The astronomical phenomena, e.g., the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, continued to “jump” in the calendar. Their dates also “slipped” backward in the calendar by an average of 1 day per year.

The situation was aggravated because the priests who kept the calendar did not follow the calendar rules. The 22 or 23 extra days (intercalation) prescribed every two years were applied irregularly.

The Roman calendar was “destroyed” so much that Caesar had to add 67 extra days to the year 46 BC (in addition to the required 23 days). As a result, the “last year of confusion” (Ultimus annus confusionis) was 445 days.