If my hypothesis were correct, it would have many implications for our today’s view of history.

I will highlight just three of these consequences here.

- The existence or duration of the Dark Middle Ages.

Life could not have stopped when the Western Roman Empire collapsed (in AD476, or according to the present hypothesis, in 696CE). Not everything sank into the “Dark Middle Ages”!

On the contrary, new forces and ideas came into play in the power vacuum. The local leaders of the formerly conquered peoples created new and smaller centres of power.

This is what happens after the fall of great empires (e.g., in Europe after World War I or after the fall of the Soviet Union). The accumulated knowledge in technology, architecture, arts, and literature does not go into “dark nothingness” but instead gets a new impetus locally.

The beginning of the Middle Ages may seem “culturally dark” because it was not possible to falsify the historical chronology in an all-encompassing way! It is easy to ‘invent’ and ‘insert’ fictitious rulers and popes, to ‘rewrite’ descriptions of earlier battles with fictional, different locations and warlords. Still, it is impossible to make up for the human works and creations missing for so long! And there has been a severe lack of archaeological “human artefacts” for an extended period after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD476.

The ‘darkness’ was mainly manifested in the absence of stable state structures in Europe. The power struggles intern and between the many new regional centres led to long-time, chaotic economic conditions and poverty.

I think that only in this sense is the adjective “dark” justified.

In my opinion, the Dark Middle Ages did not exist as we view it now!

At the beginning of the medieval era, there was only a shorter, opaque period of history. The length of this period could be extended almost imperceptibly by inserting 220 years of historical events that never took place.

The Merovingian period, for example, could start earlier, as accepted today or could be extended by 220 years by utilising false documents. This made it appear that the Carolingians had seized power from a more remarkable, earlier dynasty. No other relatively strong power existed in Europe at the time.

- The Islamic time reckoning and the present hypothesis.

The Islamic calendar is based on the lunar month and uses slightly shorter years than the Julian/Gregorian calendar. Its starting date is 16 July AD622.

The Islamic time reckoning is independent of and is parallel to AD time. As shown earlier, the Islamic time reckoning “recounted” from today seems correct.

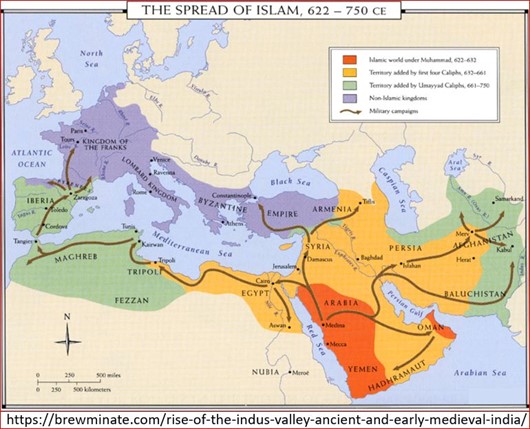

It is a known fact that Mohammed and his successors established a vast “Muslim religious empire” in about 100-120 years, stretching from Western India, Egypt, North Africa, and Iberia to the present-day south of France (Narbonne). This empire was united only in religious terms and consisted of several independent caliphates, usually allied, sometimes temporarily at enmity.

Islamic time reckoning was not established until about a century after the death of Mohammed, around the time of the confusion of AD time, but going back to the age of the Prophet Mohammed. Of course, it was synchronised with our erroneous AD calendar centuries later. So, the confusion of the AD time did not affect Islamic time.

According to our current calculations, the Islamic wars of conquest and expansion of religion began some 156 years after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, in AD632 (476+156=632).

If the present hypothesis of inserting 220 years is correct, then the Islamic conquests began 64 years before the fall of the Western Roman Empire, whose new year is 696CE and contributed to the fall of Rome. (696-64=632)

The Muslims conquered the New Persian Empire and the area around the Aral Sea to the north of it, most of the former Scythian-Hun Empire, and the former Parthia south of the Caucasus.

Many of the mixed-race peoples living there have converted to Islam.

However, most of these eastern peoples fled northwest of the Caspian Sea, and the southerners fled north through the Caucasus valleys. Then both masses of people, united under Hun leadership and the Hun collective name, marched westwards. Attila’s short-living empire of many nationalities was formed and held together by the genial warlord.

This means that the Islamic armies in the Mediterranean and Attila’s Huns in the north surrounded and almost simultaneously attacked and liquidated the Western Roman Empire in the mid-late 7th century. The Western Roman Empire was brought to its knees soon in the trap of this “huge pincer”.

- A link between Attila the Hun and the Avar history of Hungary.

Being Hungarian, I cannot leave without highlighting the most exciting consequence for the Hungarians, which is very important for the history of Hungary in the Carpathian Basin.

According to the old Hungarian chronicles, the ruling family of the Árpád House, the “conquerors” of the Carpathian Basin, referred to themselves as “home returning descendants of Attila”. The term “home-occupation” (in Hungarian “honfoglalás”) was “posthumous introduced” many centuries later. A part of Attila’s folk remained in the Carpathian Basin; some groups returned temporarily to the East, to Levedia.

Attila’s genealogy is thought to be familiar in the chronicles. However, the historically accepted elapsed period is too long for the eight generations considered as known: 845-406=439 years, 54-55 years would be the duration of a generation-change.

If history is 220 years shorter as claimed in the current hypothesis, the Attila-Árpád lineage (according to the Old Hungarian chronicles) becomes understandable and acceptable.

Attila (as we know it today) was born around AD406 and died in AD453.

The years of the life of Attila and his descendants are, to a good approximation, as follows:

*Attila born 626CE (406+220 = 626), died 673CE **Irnik/Ernák/Csaba 660CE youngest son (1st wife, Réka) ***Kovrát/Kuvrat/Hovratu 687CE (Avar ruler) ****Kuber/Küber/Kuver/Csaba 714CE fourth son of Kovrat *****Ed 741CE (Avar ruler in Levedia, north of Black Sea) ******Ügek 767CE - died after AD818 ******Előd-Levedi AD793 - ... *******Álmos AD819 - AD895 *********Árpád AD845 - AD907

The years ending with CE indicate the estimated year of the births and the year of Attila’s death, as suggested by the present hypothesis. AD-years mark the known years.

For Attila’s late-born son Csaba, I calculated a generation-year difference of 34 years, and for the other descendants, I figured a generation-year difference of 26-27 years.

There were eight generations between Attila and Árpád. The Attila-Arpád generation gap resulting from the above is 845-626 = 219 years.

On average, 229/8 = 27.375 years/generation is quite realistic.

The essential primary data of the old Hungarian chronicles, the "gestas" must be correct because the Attila-Arpád family tree is reasonably accurate considering my new time scale.

This also means that the Avars could have been a remnant of Attila’s people in the Carpathian Basin, as Gyula László, professor of archaeology, assumed in his book “Double Home-Occupation”.

Professor Gyula László assumed that the Avars, as “first Hungarian conquerors”, had already occupied the Carpathian Basin around 670CE. This is modified only because, at the time, he assumes, Attila himself had already occupied the Carpathian Basin. After Attila’s sudden death in 673CE, a larger group of Hun-Hungarians remained, whom the foreign environment renamed the Avars. Presumably, Attila’s remaining people have been renamed Avars to create an “apparently new, different” folk. The Carolingians may have fought “virtual victorious” phantom battles against the Avars that never happened (Little Pippin, then his son Charlemagne, then his son Pippin, at the invitation and blessing of the Pope). Fictitious events partially filled in the historical time gap.

It also follows from above that one of the essential years of Simon Kézai’s “Gesta” is correct, and it takes on a new meaning. In his book “Gesta Hungarorum”, Simon Kézai placed in the 700th year of the Lord the “gathering” of the Huns at the river Tisza. This military council had decided to invade the Carpathian Basin by the “Hun-Hungarians” However, Kézai did not specify how he used the word Lord, Hungarian “Úr.”

The word Lord (in the same way as in modern Hungarian, or even its equivalent dominus in Latin) could refer to the Parthian state-founder “Úr Arsaces I” and the Lord Jesus Christ, as Sándor Szekeres has claimed. According to Szekeres, the 700th year of the “Lord of Gesta” is the UR700 year of the Parthian calendar. Very importantly, Szekeres also proves that Kézai confused the year of the Huns’ invasion with the year of Attila’s death.

The history of the Parthian Empire and the Roman Empire is closely linked by their battles fought and documented by the Romans.

If the history of Rome took place 220 years closer to the present day, the history of Parthia is also closer to us in time.

Accordingly, the 1st year of the Parthian UR time is not BC247, as we think today and as accepted by Szekeres, too, but 27BCE (247-220= 27)

Counting from the year 27BCE, the UR700, according to our new, advanced time reckoning, is: UR700-27 = AD673 = 673CE.

This is the same as the year we have given above for the year of Attila’s death!

Consequently, the Huns did not invade the central and western regions of Europe at the beginning of the fifth century but first 220 years later, after AD620.

It seems that Kézai, in his Gesta, was using the Parthian time reckoning, as Sándor Szekeres has stated.

Nevertheless, Kézai was right in his Gesta Hungarorum, by using the original years of the Parthian calendar, starting in 27 BC, i.e., in its not yet antedated, ancient form !