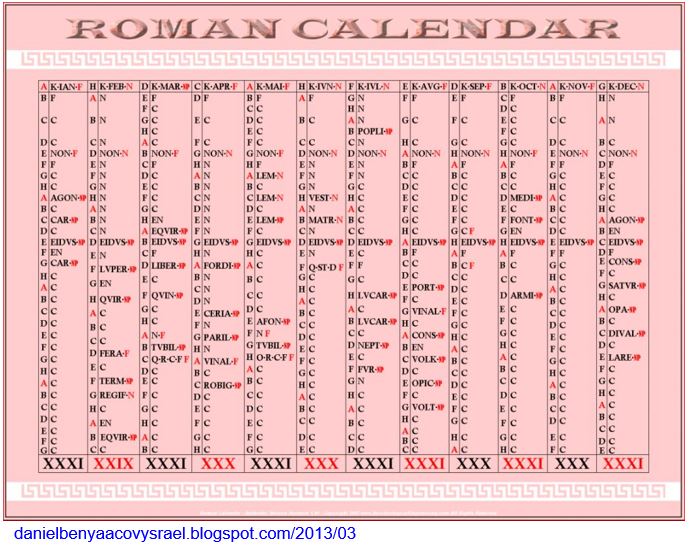

It is advisable to take a “short detour” here to survey the structure and logic of the Roman months, which is very unusual for us. The Roman calendar (according to ancient traditions already long before Caesar’s time) recorded only three important reference days per month.

These reference days were the following: K (Kalendae, Calendae), NON (Nonae) and EID (Idus, Eidus).

In the old lunar calendars, Kalendae meant the day of the appearance of the new crescent moon visible to the naked eye, i.e., the first day of the new month, the day of the announcement of the month.

The day of Kalendae was “proclaimed” by the priests at the beginning of each month, announcing the length of the month and calling for the payment of debts etc. (the Latin word “calo” means to proclaim). The term calendar derives from his Latin word and is used in many languages (English Calendar, German Kalender, Old Hungarian Kalendárium, etc.).

In ancient times, even astronomers considered the already visible new moon crescent as the new moon, the day of Kalendae, instead of the invisible astronomical new moon about two days before. (The binoculars were not yet known).

Idus originally meant the middle of the month when the full moon fell.

The Nonae, introduced later, represented the ninth day, calculated “inclusive” and backwards from Idus. (8th day according to our present method of calculation), the day of the first crescent, and indeed the waxing crescent.

The days were generally (with few exceptions) identified by these reference days but counted backwards and inclusive. In fact, the days missing until the specified reference day were counted.

For example, the birthday of Emperor Augustus, September 23, is called the 9th day before the Kalendae of October (ante Diem IX Kalendae Octobres) in the 30-day month of September. (8th day before the Kalendae of October for the old 29-day month of September.)

Due to changes in the lunar calendar, the old astronomical significance of the reference days disappeared. Because of the extended length of months, there was only infrequently a new moon on the day of Kalendae.

Caesar, however, mainly from political considerations, retained the tradition of reference days in the calendar structure, especially the role of Kalendae but only as the starting day of the month. But still, according to sources, in the year the new calendar was introduced, January 1 was the first new moon day after the winter solstice of the previous year.

It sounds very logical because this way, the first Kalendae day of the new calendar of Caesar announced not only the first month of the new calendar but also the new calendar itself.

In my opinion, starting the new calendar with Kalendae on the new moon was particularly important. It symbolised that the traditional date reference days and calendar structures were appreciated and retained.

As we have seen, this calendar setting may have been achieved by adjusting the length of the previous “last confused year”. (As it is known today: 46BC, 445 days)

On the other side, today, we know from astronomical retro-calculations that there was no observable new moon in the Roman sky on January 1, 45BC. The barely visible, very narrow new moon crescent appeared in the Roman sky only on January 3 in 45BC.

This consideration alone is enough to question the acceptance of BC 45 as the realistic first year of the Julian calendar! Namely, the new moon crescent was only observable in 53BC, 34BC, 15BC, AD5, AD24, AD43, AD62 (etc., according to the 19-year Metonic cycle) on January 1 in Rome.