Claudius Ptolemy was a Greek staff member of the “Great Library of Alexandria” (Musaeum or Mouseion), the knowledge centre of antiquity. Ptolemy was neither an innovator, researcher, or practical scientist but rather a “systematic mind”, an “integrator”.

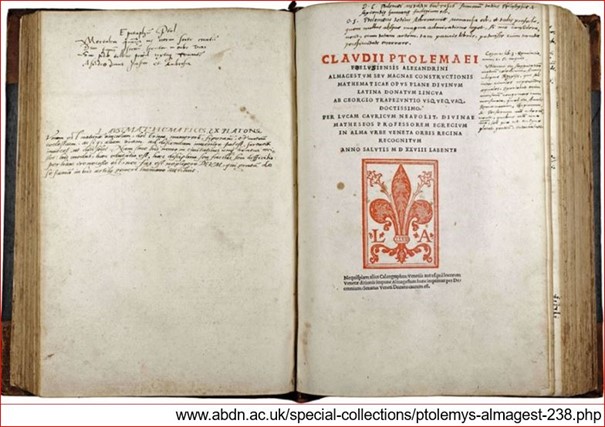

As a diligent reader and scholar of the scientific achievements of his time, he collected and integrated the accepted teachings of mathematics and astronomy in his magnum opus, “Syntaxis Mathematica“. The “Magna Syntaxis” was later called “Almagest” from the Arabic word for “greatest”.

Hipparchus’ ideas and calculation data on precession are known from Ptolemy’s Almagest, which the author completed around 150 AD, as we know it today.

Unfortunately, Hipparchus’ works have been lost. (Except the so-called “Phaenomena” commentaries).

Furthermore, “the source of the source”, Almagest, has been lost, too.

Ptolemy’s work was written in Egyptian Greek and first only translated into Latin in the 12th century on the basis of an earlier Arabic translation. Earlier fragments of ancient Greek copies also surfaced in the 15th century.

The Almagest had defined astronomers’ “geocentric world view” for over a thousand years. Unfortunately, it has displaced and almost forced into oblivion all other ideas such as the “heliocentric theory”, previously known in Mesopotamia.

It is particularly noteworthy that despite the absence of the original work, Almagest’s astronomical claims were for many centuries regarded by the Roman Church and scholars alike as indisputable astronomical truth. Despite (or perhaps because of?) Almagest (following Hipparchus’ worldview) held to the geocentric theory; it became a long-living paradigm of astronomy.

An essential “annexe” of the Almagest is the so-called “star catalogue“, which gives the celestial positions of hundreds of stars in tabular form based on data from Hipparchus. (Almagest’s “Star Catalogue”: coordinates of 1022 stars, the vast majority of which are derived from Hipparchus, as we know it today.)

Of course, from the voluminous Almagest, we highlight and examine only the issues of interest to us.

The change in stellar coordinates relative to AEQ and VEQ due to precession is most apparent and measurable in the case of fixed stars along the ecliptic (e.g. SPICA, REGULUS).In antiquity, due to the slow rate of precession change, this observation could only be made by comparing the data from old and new measurements repeated centuries later. Hipparchus also compared his own data with the old data of his predecessors. And Ptolemy compared the measured data of his own time with those of Hipparchus.

Ptolemy did not mention any historically identifiable date for Hipparchus’ years of life (190BC-120BC), these years being derived from a posterior astronomical countdown.

It is now reckoned that Hipparchus compared the data of his astronomer predecessor Timocharis and of earlier astronomers in New Babylonia (Chaldee, registered around 280BC) with his own data (measured around 128BC).

It is also assumed that the astronomical data of Ptolemy’s own time were taken from measurements made in or around AD138. Probably, they were not Ptolemy’s own measurements but the somewhat earlier results of a more practical contemporary.