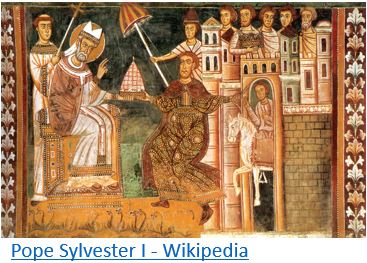

The picture on the left shows the “protagonists” of the First Council of Nicaea (AD325), Pope Sylvester I. and Constantine I. (the Great), the first Roman emperor to be baptised.

Twelve years earlier, Constantine the Great had enacted the “Edict of Milan”, which accepted Christianity with state benevolence in the Roman Empire.

By the time of the First Council of Nicaea, the Roman Church had long been aware of the flaw in the Julian calendar that VEQ day was consistently moved back one day every 128 years. This coincided with the fact that Christians had long wanted to move away from the old Jewish Passover method of calculating the Easter date.

To make the VEQ day clear for Easter date calculation (computus), the synod formally fixed the date of VEQ day by church decree to 21 March, thus making it independent of the actual astronomical date. (It was gradually introduced after the year of the synod, the exact timetable for its introduction is unknown.)

The synod could have chosen any day near 21 March, but the Church does not choose arbitrarily, and the Church usually decides according to its own traditions. Even when they informally set VEQ Day, they probably chose a date they calculated as VEQ Day in the year of Jesus’ crucifixion.

The year of the synod as adopted today is AD325.

In AD325, the date of VEQ is 20 March, 13:50.

This is when the VEQ fell in Rome for a long time (AD308-AD347) on 20 March.

Looking back from the year AD325, the Church would also have seen that the day of VEQ should have originally fallen on 22-23 March, around the year of Jesus’ crucifixion.

It is, therefore, logical to assume that in AD325:

– the Church (probably following its own tradition) either set the VEQ on 22 March, since around the year of Jesus’ crucifixion (AD20-AD50), the VEQ fell predominantly on 22 March. (In AD33 and AD36, the VEQ fell on 22 March, and it has continued to shift towards the stable on 22 March);

– or perhaps the synod would have set the VEQ day for AD325 as 20 March, since in the years around AD325, the VEQ day fell decades-long on 20 March, as seen above.

This means that AD325 is out of the question, as the year of the First Council of Nicaea, because in AD325, the synod would hardly have chosen 21 March as the official VEQ day.

After transforming AD325 two-hundred-twenty years closer to us, we come to 545CE, the new year of the Council of Nicaea.

In 545CE, the VEQ was pushed back to 18 March, 20:29.

Around 545CE, VEQ fell every two years, alternately on 18 or 19 March.

Accordingly, it is logical to assume that in 545CE:

– following the church tradition, the synod probably would have fixed VEQ day on 20 or 21 March, since around the year of Jesus’ crucifixion, 256CE, VEQ fell every two years alternately on 20 or 21 March. Probably they counted back to 256CE and found with a small error that VEQ fell on 21 March that year.

– or perhaps the synod could have fixed the VEQ day on 18 March because of the accumulated error in the Julian calendar for AD545, since in the years around AD545, the dominance of 18 March as VEQ day was imminent.

Bishops and prelates usually decide to follow the traditions of the Roman Church, and this may have been the case in Nicaea, too!

The Roman Church may have known that VEQ was initially on 21 March in the Julian calendar. This knowledge may also influence their decision for 21 March as a formal VEQ day for computus.

The consequence: the date fixing by the church has made it possible to produce Easter tables connected loosely to astronomical reality! The fixing of the VEQ date for 21 March made it easier for Beda to compile retroactively false Easter tables since Beda's hands were not tightly bound by the actual date of the astronomical VEQ day.

The First Council of Nicaea had not yet considered a calendar reform. Formalising the VEQ day was much easier than a hasty calendar reform would have been.

Setting the VEQ date to 21 March solved the issue of calculating the Easter date created by the backsliding of the VEQ date in the Julian calendar. The fixing of the VEQ day kept Easter as a movable holiday but also separated it from the “Jewish Passover” (which was strictly linked to the astronomical VEQ).

Conclusion: The Church's decision to set the VEQ Day on 21 March means to me that the 220-year-later 545CE is more appropriate as the year of the First Council of Nicaea than AD325.